ENGLISH VERSION BELOW

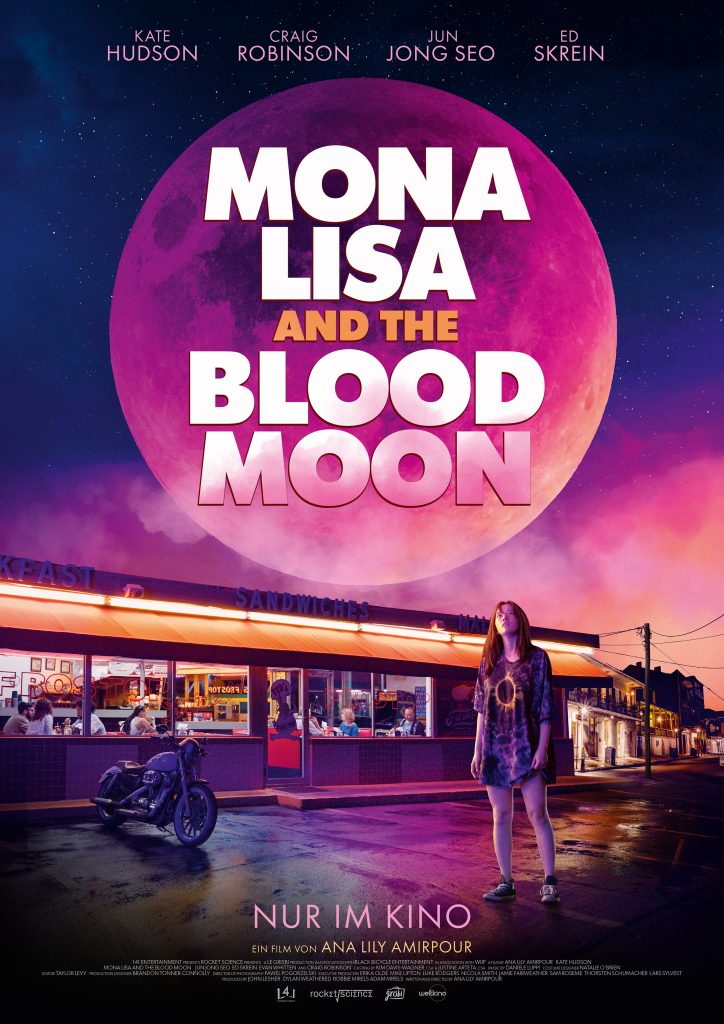

Regie: Ana Lily Amirpour

Cast: Jun Jong Seo, Kate Hudson, Craig Robinson, Ed Skrein, Evan Whitten

Musik: Daniele Luppi

Produktion: USA 2021

Lauflänge: 106 Minuten

Kinostart: 6. Oktober 2022

“Mona Lisa, Mona Lisa men have named you. You′re so like the lady with the mystic smile. Is it only ‚cause you′re lonely they have blamed you. For that Mona Lisa strangeness in your smile?” “Mona Lisa and the Blood Moon” fängt an mit jenem Lied, das Nat King Cole berühmt gemacht hat, 1950. Das war schon eine Coverversion, danach gab’s noch etliche. Diejenige, die jetzt über der Eingangssequenz schwebt, ist a capella, ätherisch, unheimlich – und die besungene „strangeness“ in Mona Lisas Lächeln bekommt hier etwas Bedrohliches, Beängstigendes. Die Bilder derweil zeigen den nächtlichen Sumpf von Louisiana, die Wälder, der ruhig daliegende dunkle Wasserspiegel.

Louisiana, Louisiana… Weiß ich zu wenig darüber. Liegt am Golf von Mexiko. Östlich von Texas. New Orleans ist die größte Stadt. Louisiana wird, sagt Wikipedia, „Pelican State“ genannt, genau, wegen der Vögel – oder „Bayou State“, wegen der Sümpfe. Bayou: stehendes oder langsam fließendes Gewässer, im Mississippi-Delta wohl häufig der einzige Verkehrsweg (siehe „Blue Bayou“ von Roy Orbison, später Linda Ronstadt. Oder Paola, 1978 – die Frau von Kurt Felix). Mir ist aber so, dass ich Louisiana aus Filmen kenne – und so ist das auch. Wikipedia zählt Louisiana-Filme auf: Angel Heart (Alan Parker, 1987), Dead Man Walking (Tim Robbins, 1995), Down by Law (Jim Jarmusch, 1986), Mississippi Delta (Phil Joanou, 1996), The Big Easy (Jim McBride, 1987), Wild at Heart (David Lynch, 1990), Beasts of the Southern Wild (Benh Zeitlin, 2012). Und prompt möchte man so etwas wie eine Gemeinsamkeit unter Louisiana-Filmen ausmachen: Schwermut, Schwüle, Melancholie, Betrübnis, Trübsinn. Und den Louisiana-Soundtrack meint man mit Klageliedern einerseits und Froschquaken und Grillenzirpen andererseits zu verbinden.

Und genau dieses Zirpen und Quaken hören wir, dann wechselt das Bild nach innen, in eine Psychiatrie, eine geschlossene Anstalt, in eine gepolsterte Gummizelle. „Mona Lisa“ verhallt derweil in der Ferne. Die Insassin der Zelle ist, ja: Mona Lisa, so wird sie genannt. In Zwangsjacke. [Wie hieß nochmal der Soderbergh-Film, mit iPhone gedreht, in der Irrenanstalt spielend? Erinnert mich visuell an diese Irrenhausszenen: Unsane! 2018, lief auf der Berlinale, einer der letzten Fox-Filme, mit denen ich damals zu tun hatte] Sie, Mona Lisa, erwacht, kommt zu sich, ist beängstigt. Kraucht umher, wie ein wildes, verletztes Tier (Woran erinnert mich das? Woran erinnert mich das? Hat jemand Doha Cats „Say so“-Hardrockversion bei den MTV European Music Awards 2020 gesehen? Dann bitte bei Youtube, 8 Millionen Views, nachholen). Jun Jong Seo ist die Schauspielerin, die Mona Lisa spielt (siehe Lee Chang-dongs Film „Burning“ aus dem Jahr 2018; Mona Lisa ist ihr US-Debüt).

Von draußen naht, entspannt ein Liedchen trällernd die Wärterin, läuft durch die Anstalt, schließt den – aha – Hochsicherheitstrakt auf, Mona Lisa hört sie sich nähern. Sie kommt zu ihr in die Zelle, glaubt dass Mona Lisa immer noch machtlos in ihrer Welt versunken ist, nennt sie „stupid“, haut ihr auf die Schultern. Man fürchtet schon. „I asked you a question, stupid“, insistiert die kaugummikauende Wärterin und schubst sie. Die Nägel muss sie ihr schneiden, damit sie mit denen nichts anstellen kann. Und dann passiert Sonderliches: Mona Lisa hat telekinetische Kräfte, psychische Mächte. Sie zwingt die beschränkte Wärterin dazu, sich mit der Nagelschere ins Bein zu stechen. Immer wieder. Blutig wird’s. Mona Lisa lässt sich von der Wärterin befreien, schnappt sich die Schlüssel, schleicht an einem anderen, von Telenovelas und Chips abgelenkten Wärter vorbei, nein: Sie spricht ihn an, fordert die Herausgabe der Kartoffelchips, schlägt sich den Magen voll, doch er kommt auf die blöde Idee, den Alarmknopf zu drücken, was, ich kürze ab: schmerzhaft für ihn endet.

Und endlich ist sie draußen. Wo der Vollmond scheint. Blutmond, sagt der Filmtitel. Mit ihrer (wie ich finde) modisch lässig erscheinenden Zwangsjacke, die jetzt locker runterhängt, trifft sie gleich um die Ecke auf ein paar Jungs und Mädels, die feiern und saufen, sie geben ihr ein Bier ab. Die eine junge Frau ist hilfreich, kümmert sich um ein paar Schuhe für die barfüßige Entflohene und weist ihr den Fluchtweg nach New Orleans, hinter dem Zaun an den Sümpfen vorbei, den Schienen entlang, eben bis New Orleans. Immer noch schweigend macht sich Mona Lisa auf den Weg. Am Sumpf vorbei, die Gleise entlang, durch die Blutmondnacht, bis nach New Orleans, wo ein Feuerwerk stattfindet, das sie mit Verwunderung wahrnimmt. Staunend läuft sie durch die Nacht in der Stadt, Straßenbahn, Palace Café, Geschäfte. Derweil wird schon per Funk vor einer gewalttätigen Ausgebrochenen gewarnt. Psychisch labil, schizophren, sehr gefährlich. Im Restaurant sitzt ein Polizist (Craig Robinson), er bekommt Mona Lisas Bild aufs Handy, damit er sich in Acht nimmt und sich nach ihr umschaut. Nach dem Essen geht der Cop nach draußen, öffnet noch seinen Glückskeks: Forget What You Know. Er steht auf dem einsamen Parkplatz des Restaurants, wird von seiner Leitstelle angefunkt. Harold heißt er. Zwei Unruhestifterinnen vor einem Supermarkt, dem Esplanade-Market, soll er auf die Spur gehen. Dasselbe Ziel hat zufälligerweise auch Mona Lisa, die dort auf vor dem Geschäft Herumlungernde stößt, die sich für ihre Aufmachung interessieren und glauben, dass sie was mit Drogen am Hut hätte. Sie will aber eher deren Pommes essen.

Einer der Typen (Ed Skrein), mit komischer Steampunksonnebrille, folgt ihr ins Geschäft und hilft ihr aus der Patsche, als sie merkt, dass sie ohne Geld keine Erdnussflips und kein Bier mitnehmen kann. Er zahlt für sie, will mit ihr quatschen, bewundert ihr Outfit, das echt „next level“ sei. Und jetzt sagt sie das erste Mal etwas, nach 17 Minuten Film, weil sie nämlich ihr Knabberzeug haben will. Das hat aber noch der Brillentyp. Er nimmt sie mit zu seinem Auto, psychedelische Discokarre. Man nenne ihn Fuzz, weil er so weich sei. Und flauschig. Er will was von ihr, sie küssen, damit kann sie gar nichts anfangen. Sie will nur die Flips.

Derweil taucht der Cop auf, der sich um die beiden Betrunkenen Frauen kümmern soll, die man bisher nur kotzend im Hintergrund wahrgenommen hat. 100$ Strafe will Harold, sowas kostet das, wenn man auf den Gehsteig kotzt, auch wenn man Geburtstag hat. Mona Lisa fordert Fuzz‘ T-Shirt ein, er weiß nicht, was sie will, wir auch nicht, dann verdrückt sie sich – und nun wird Harold auf sie aufmerksam. Inzwischen hat sie Fuzz‘ T-Shirt an und nicht mehr die auffällige Zwangsjacke. Er weiß, wer sie ist, will sich um sie kümmern, sagt er sanftmütig, aber zur Sicherheit müsse er ihr dazu Handschellen anlegen. Doch dafür hat sie kein Verständnis. Telekinetisch lässt sie ihn seine Handschellen fallen, seine Dienstpistole nehmen, in die Luft schießen – und dann in sein Knie. „Ich gehe da nicht wieder hin“, sagt die entschlossen.

Harold landet im Krankenhaus, Mona Lisa zieht weiter, hat immer noch Hunger und stößt bei einem Fastfoodrestaurant auf die Stripperin Bonnie (Kate Hudson), die gerade Ärger mit einer prügelfreudigen Eifersüchtigen, Irene, hat. Mona Lisa kommt zur Hilfe, Bonnie erkennt ihre Fähigkeiten und nimmt sich nun ihrer an. Sie gibt ihr zu essen, nimmt sie an ihren Arbeitsplatz im Stripclub mit, erklärt ihr, was sie dort macht und was die Männer da wollen. Mona Lisa hat keine Ahnung, wie das in der Welt so läuft, offenbar kannte sie bisher nur die Anstalt, in der sie ihr Leben verbracht hat. Und da „hilft“ Mona Lisa den Männern eben dabei, mehr Dankbarkeit für Bonnies Arbeit zu zeigen und ordentlich Trinkgelder zu geben. Endlich verdient sie vernünftig Geld, schließlich muss sie sich auch um ihren 10-jährigen Sohn Charlie (Evan Whitten) kümmern.

Doch zwischen den beiden Frauen bleibt es nicht dabei, ein paar Männer im Stripclub auszunehmen. Bonnie nutzt Monas Kräfte für richtige Raubzüge. Inzwischen forscht der nun hinkende Harold nach Mona Lisa und erfährt mehr über ihre schwierige Vergangenheit, über ihre Herkunft und darüber, warum sie in der geschlossenen Anstalt gelandet ist. Und zwischen der scheuen Mona und dem wütenden Charlie, der es nicht leicht hat und von Nachbarskindern gemobbt wird, entwickelt sich nun eine zarte, für beide hilfreiche Freundschaft.

Nun wird Tempo herausgenommen – aus Charlies Leben, aus Monas Leben, aus dem Film, und das ist erfreulich, mussten wir mit den Protagonistinnen bisher ein atemberaubendes Tempo mitgehen. Charlie zeichnet Mona, sie hört das erste Mal, dass es so was wie Freunde, Leidenschaften, Interessen gibt. Das fasziniert sie…

Der Film funktioniert, weil man mit der scheuen aber machtvollen Mona Lisa mitfühlt, man ist auf ihrer Seite, wenn sie sich gegen die schonungs- und ausweglose Psychiatrie auflehnt, auf der Seite der Stripperinnen gegen die rücksichtslosen Männer ist, wenn sie auf Charlies Seite gegen die gemeinen Mitschüler ist. Mona Lisa ist die Verkörperung von Allmachtsphantasien gegen die Ungerechtigkeiten der Welt. Dies wird aber schwierig, wenn Bonnie beginnt, ihre Kräfte auszunutzen und übers Ziel hinauszuschießen. Und gegen Schluss wird’s dann auch wieder arg konventionell.

Insbesondere das Personal des Films, der halbseidene, schrille Fuzz, der unbeholfene Cop Harold, die abgebrühte Stripperin Bonnie und die ganzen weiteren halbgaren Nebenfiguren aus dem Umfeld der Drogen- und Rotlichtszene machen den Film zu einem unterhaltsamen B-Fantasy-Movie. Aber im Zentrum der Handlung steht die ungewöhnliche Superheldin Mona Lisa.

Vielleicht lässt die Verknüpfung der Mona Lisa-Figur ins Genregerüst der Hauptdarstellerin Jun Jong Seo nicht allzuviel Raum dafür, mit ihrer Rolle zu brillieren. Allzusehr hat sie jederzeit die Möglichkeit, der Bredouille mittels ihrer Kräfte zu entkommen. Kate Hudson als Bonnie hingegen kann ihre Genrefigur vor dem Hintergrund gesellschaftlicher Wirklichkeit entfalten und im sozialen Gefüge der Filmwelt aufleben lassen. Insofern ist ihre Rolle eigentlich die, die man als die stärkere, echtere, einprägsamere aus dem Film mitnimmt. Die schon beschriebene Schwermut Louisianas, die sich auch in der Halbwelt von New Orleans fortsetzt, macht den Film schließlich wiederum zu einem weitgehend funktionierenden, außergewöhnlichen, morbiden und kurzweiligen Trash-Superheldenfilm.

MONA LISA AND THE BLOOD MOON ist Ana Lily Amirpours dritter Film, nach A GIRL WALKS HOME ALONE AT NIGHT (2014) und THE BAD BATCH (2016). In ihrem Statement zu MONA LISA lässt sich die Verknüpfung ihrer Filmheldinnen mit Machtfantasien ihrer Kindheit ablesen: „Die Fantasy-Filme, die ich gern als Kind geschaut habe, haben den Außenseitern Macht verliehen. Darin fand ich Helden, die mir das Gefühl gaben, gesehen zu werden, und die mich in meinem Streben nach persönlicher Freiheit bestärkt haben. Ich liebe es, Helden zu erschaffen, besonders mit einem fantastischen Element.“

Mona Lisa wird damit zur Projektionsfläche der Regisseurin, so wie man in die „echte“, im Louvre hängende Mona Lisa ja auch so viel hinein- und herauslesen kann. Die Mona Lisa da Vincis sei undefinierbar, sie „ist ein Mysterium, das viele Formen annehmen kann; sie kann kindlich sein, monströs, feminin, maskulin, gefährlich, aber auch verletzlich. Das Schöne am Kino und am Genre ist, dass alles möglich ist, und Magie real wird. Es gibt dir die Möglichkeit, dir die Art von Superkraft auszumalen, die du gerne hättest. Niemand kann Mona Lisa physisch etwas anhaben. Sie hat die komplette Kontrolle. Dadurch besitzt sie die Freiheit, alles zu sein, was sie will“, sagt die Regisseurin.

“Many dreams have been brought to your doorstep,” endet schließlich der Mona-Lisa-Song. “They just lie there, and they die there. Are you warm? Are you real, Mona Lisa? Or just a cold and lonely, lovely work of art?”

ENGLISH VERSION

“Mona Lisa, Mona Lisa men have named you. You’re so like the lady with the mystic smile. Is it only ‚cause you’re lonely they have blamed you. For that Mona Lisa strangeness in your smile?” “Mona Lisa and the Blood Moon” starts with the song that made Nat King Cole famous, 1950. That was a cover version, there were many more after that. The one now hovering over the opening sequence is a cappella, ethereal, eerie – and the sung „strangeness“ in Mona Lisa’s smile takes on a menacing, frightening quality here. The pictures, meanwhile, show the nocturnal swamp of Louisiana, the forests, the calm, dark water surface.

Louisiana, Louisiana… I don’t know enough about it. Located on the Gulf of Mexico. East of Texas. New Orleans is the largest city. According to Wikipedia, Louisiana is called „Pelican State“, precisely because of the birds – or „Bayou State“, because of the swamps. Bayou: stagnant or slowly flowing body of water, often the only traffic route in the Mississippi Delta (see “Blue Bayou” by Roy Orbison, later Linda Ronstadt. Or Paola, 1978). But I feel like I know Louisiana from movies – and that’s how it is. Wikipedia lists Louisiana films: Angel Heart (Alan Parker, 1987), Dead Man Walking (Tim Robbins, 1995), Down by Law (Jim Jarmusch, 1986), Mississippi Delta (Phil Joanou, 1996), The Big Easy (Jim McBride, 1987), Wild at Heart (David Lynch, 1990), Beasts of the Southern Wild (Benh Zeitlin, 2012). And immediately one would like to identify something like a commonality among Louisiana films: melancholy, muggy, melancholy, sadness, gloom. And the Louisiana soundtrack is associated with lamentations on the one hand and frog croaking and cricket chirping on the other.

And it is precisely this chirping and croaking we hear, then the image changes inwards, into a psychiatric ward, a closed institution, into a padded padded cell. Meanwhile, „Mona Lisa“ fades away in the distance. The occupant of the cell is, yes: Mona Lisa, that’s what she’s called. In straight jacket. [What was the name of the Soderbergh film again, shot with iPhone, set in the mental asylum? Reminds me visually of those madhouse scenes: Unsane! 2018, ran at the Berlinale, one of the last Fox films I was involved with at the time] She, Mona Lisa, wakes up, comes to, is scared. Crawls around like a wild, injured animal (What does this remind me of? What does this remind me of? Has anyone seen Doha Cat’s „Say So“ hard rock version at the MTV European Music Awards 2020? Then please catch up on Youtube, 8 million views). Jun Jong Seo is the actress who plays Mona Lisa (see Lee Chang-dong’s 2018 film Burning; Mona Lisa is her US debut).

The warden approaches from outside, sings a relaxed song, walks through the facility, unlocks the – aha – high-security wing, Mona Lisa hears her approaching. She comes to her in the cell, believes that Mona Lisa is still powerless in her world, calls her „stupid“, slaps her on the shoulder. One fears. „I asked you a question, stupid,“ insists the gum-chewing guard and pushes her. She has to cut her nails so she can’t do anything with them. And then something special happens: Mona Lisa has telekinetic powers, psychic powers. She forces the restricted guard to stab her leg with nail scissors. Again and again. It gets bloody. Mona Lisa lets the guard free her, grabs the keys, sneaks past another guard who is distracted by telenovelas and chips, no: she speaks to him, demands that the potato chips be handed over, fills her stomach, but he comes up the stupid idea of pressing the alarm button, which ends up being painful for him.

And finally she’s out. Where the full moon shines, Blood moon, says the film title. With her (in my opinion) fashionably casual-looking straitjacket, which is now hanging loosely, she meets a few boys and girls just around the corner who are partying and drinking, they give her a beer. One young woman is helpful, takes care of a pair of shoes for the barefoot escapee and shows her the escape route to New Orleans, behind the fence, past the swamps, along the rails, straight to New Orleans. Still silent, Mona Lisa sets off. Past the swamp, along the railroad tracks, through the blood moon night, to New Orleans, where fireworks take place, which she observes with amazement. Amazed, she walks through the night in the city, tram, Palace Café, shops. In the meantime, a radio warning of a violent escapee is already being issued. Mentally unstable, schizophrenic, very dangerous. A policeman (Craig Robinson) is sitting in the restaurant, he gets Mona Lisa’s picture on his cell phone so that he can be careful and look around for her. After the meal, the cop goes outside and opens his fortune cookie: Forget What You Know. He’s standing in the restaurant’s lonely parking lot, being radioed by his control center. His name is Harold. He is supposed to track down two troublemakers in front of a supermarket, the Esplanade Market. Mona Lisa happens to have the same goal, when she finds people loitering outside the store, interested in her getup and believing she’s into drugs. But she would rather eat their fries.

One of the guys (Ed Skrein), wearing weird steampunk sunglasses, follows her into the store and bails her out when she realizes she can’t get peanut flips and beer without money. He pays for her, wants to chat with her, admires her outfit, which is really „next level“. And now she says something for the first time, after 17 minutes of film, because she wants her snacks. But the glasses guy still has that. He takes her to his car, psychedelic disco cart. They call him Fuzz because he’s so soft. And fluffy. He wants something from her, kiss her, she can’t do anything with that. She just wants the flips.

Meanwhile, the cop appears who is supposed to take care of the two drunk women, who until now have only been seen throwing up in the background. Harold wants a $100 fine, that’s what it costs if you puke on the sidewalk, even if it’s your birthday. Mona Lisa demands Fuzz’s T-shirt, he doesn’t know what she wants, neither do we, then she slips away – and now Harold notices her. She’s now wearing Fuzz’s T-shirt and no longer in the flashy straitjacket. He knows who she is and wants to take care of her, he says gently, but to be on the safe side, he has to handcuff her. But she doesn’t understand that. Telekinetically, she makes him drop his handcuffs, grab his service pistol, shoot it in the air – and then in his knee. „I’m not going back there,“ she said resolutely.

Harold ends up in the hospital, Mona Lisa moves on, still hungry, and bumps into stripper Bonnie (Kate Hudson) at a fast food restaurant, who is having trouble with a jealous, brawling, Irene. Mona Lisa comes to rescue, Bonnie recognizes her abilities and now takes her on. She feeds her, takes her to her place of work in the strip club, explains what she does there and what the men there want. Mona Lisa has no idea how things work in the world, apparently she only knew the institution in which she spent her life. And that’s where Mona Lisa „helps“ the men to show more gratitude for Bonnie’s work and to give proper tips. Finally she earns money, after all she also has to take care of her 10-year-old son Charlie (Evan Whitten).

But the two women don’t stop at ripping off a few men at the strip club. Bonnie uses Mona’s powers for real heists. Meanwhile, the now limping Harold searches for Mona Lisa and learns more about her troubled past, where she came from and why she ended up in the closed institution. And between the shy Mona and the angry Charlie, who doesn’t have it easy and is bullied by the neighborhood children, a tender friendship develops that is helpful for both of them.

Now the tempo is taken away – from Charlie’s life, from Mona’s life, from the film, and that’s gratifying, we’ve had to keep up with the protagonists at a breathtaking pace so far. Charlie draws Mona, she hears for the first time that there are such things as friends, passions, interests. That fascinates her…

The film works because you empathize with the shy but powerful Mona Lisa, you side with her when she stands up to ruthless and hopeless psychiatry, side with the strippers against the ruthless men, and when she sides with Charlie, against the mean classmates. Mona Lisa is the embodiment of omnipotence fantasies against the injustices of the world. This becomes difficult, however, when Bonnie begins to use her powers and overshoot the mark. And towards the end it gets really conventional again.

In particular, the film’s staff, the half-witted, shrill Fuzz, the clumsy cop Harold, the hard-nosed stripper Bonnie and all the other half-baked supporting characters from the drug and red-light scene make the film an entertaining B-fantasy movie. But at the center of the plot is the unusual superheroine Mona Lisa.

Perhaps the linking of the Mona Lisa character to the main actress Jun Jong Seo’s genre framework doesn’t leave too much room for her role to shine. She always has the opportunity to escape the trouble with her powers. Kate Hudson as Bonnie, on the other hand, can unfold her genre figure against the background of social reality and bring it to life in the social fabric of the film world. In this respect, their role is actually that one than the stronger, more real, more memorable one you take away from the film. The already described melancholy of Louisiana, which also continues in the half-world of New Orleans, ultimately makes the film a largely functioning, extraordinary, morbid and entertaining trash superhero film.

MONA LISA AND THE BLOOD MOON is Ana Lily Amirpour’s third film, following A GIRL WALKS HOME ALONE AT NIGHT (2014) and THE BAD BATCH (2016). In her statement about MONA LISA, the link between her film heroines and the power fantasies of her childhood can be seen: “The fantasy films that I liked to watch as a child gave outsiders power. In it I found heroes who made me feel seen and strengthened my quest for personal freedom. I love creating heroes, especially with a fantastical element.”

Mona Lisa thus becomes the director’s projection surface, just as one can read so much into and out of the „real“ Mona Lisa hanging in the Louvre. Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is undefinable, she “is a mystery that can take many forms; she can be childish, monstrous, feminine, masculine, dangerous, but also vulnerable. The beauty of cinema and the genre is that anything is possible and magic becomes real. It gives you the opportunity to envision the kind of superpower you would like to have. Nobody can physically harm Mona Lisa. She is in complete control. It gives her the freedom to be whatever she wants,“ says the director.

„Many dreams have been brought to your doorstep,“ the Mona Lisa song ends. “They just lie there, and they die there. Are you warm? Are you real, Mona Lisa? Or just a cold and lonely, lovely work of art?”